Africa has undoubted potential to be a world leader in the cultivation of cannabis and its products, but tight domestic controls and tough global regulations stand in the way of the creation of a booming multi-billion-dollar industry.

Half an hour into a State of the Nation address punctuated by familiar measures to combat a gloomy economic situation, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa flashed a wicked smile at his Cape Town audience. Miming the actions of a smoker, imaginary joint raised to his lips, he humorously confided his latest plan to kickstart sluggish growth.

“We will review the policy and regulatory framework for industrial hemp and cannabis – which will come as sweet news for our people in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu Natal – to realise huge potential for investment and job creation. Now this natural product, which our people have been farming with and harvesting for a number of purposes, is going to be industrialised – and no longer just restricted to the smoke process!” he quipped.

Despite the jocular tone, which prompted audience laughter and a smattering of applause, it was clear that the president sees the industry as a very serious proposition. The legal hemp and cannabis sector, he told the nation, has the potential to create more than 130,000 new jobs in South Africa. To further his point, he highlighted Lesotho – the small independent kingdom locked within South Africa’s landmass – as a shining example of a country already grasping the enormous opportunities of cannabis cultivation.

“Our immediate neighbour in Lesotho has moved ahead in industrialisation of cannabis in leaps and bounds, and products that can be eked out of hemp and cannabis are in great demand around the world. We want to harness this so we can unleash the energy of our ordinary farmers in the various parts of our country,” Ramaphosa said.

Forbidden plant goes mainstream

South Africa is just the latest country to turn decisively in favour of a sector which has witnessed an astonishing transition from a global shadow industry to an agro-industrial powerhouse. From medical cannabis to lifestyle supplements and recreational smoking, cultural, medical and legal change is wafting the scent of the once forbidden plant firmly into the global mainstream.

By 2023, the value of Africa’s legal cannabis market could be at least $7.1bn across nine key African countries if they legalise recreational and medical use, according to The African Cannabis Report from industry analysts Prohibition Partners. Worldwide, the Covid-19 lockdown period saw record-breaking sales of cannabis in multiple regions. Global sales of CBD (an active cannabis ingredient frequently used as a natural remedy), medical cannabis, and adult-use (recreational) cannabis topped $37.4bn in 2021, and could rise to $102bn by 2026, says the firm.

As of late 2021 only Uruguay, Canada and a handful of US states had fully legalised cannabis for adult use, but Mexico and Israel are primed to do so this year, and the Netherlands and Switzerland are preparing legal trials. Meanwhile, dozens of countries worldwide already permit cannabis for medical use and allow the sale of CBD-infused over-the-counter products, including oils, drinks and snacks.

For the many African countries that possess an ideal climate for growing the plant, these global trends represent a vibrant opportunity.

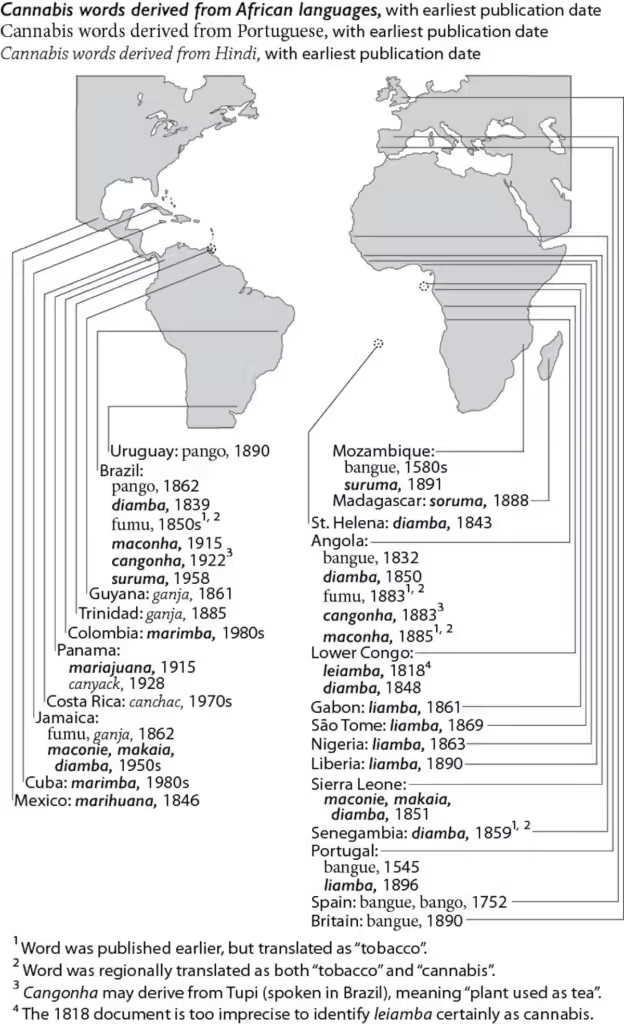

“Africa has been a leader in global production for several decades. It’s got a huge comparative advantage, the plants can grow outdoors, they can grow multiple crops per year,” says Chris Duvall, professor and chair of Geography and Environmental Studies at the Latin American and Iberian Institute of the University of New Mexico and author of The African Roots of Marijuana.

“Agricultural labour is inexpensive. Inputs are relatively inexpensive. Africa has huge potential because there’s knowledge, there’s competitive advantage just in terms of ecology.”

Yet despite Africa’s apparent suitability for widescale cultivation – the United Nations estimates that over 38,000 tonnes of cannabis are produced illegally across Africa each year – and the plant’s ingrained status in the culture of several African countries, its use remains proscribed in all but a tiny handful of African nations.

Furthermore, companies wishing to operate in the sector must navigate high startup costs, strict and ever-evolving regulations, and country-by-country legislation. Some critics fear that only cash-rich foreign firms will be able to take advantage of Africa’s market, locking out domestic producers and erecting a familiar model based on raw material extraction with limited in-country value addition.

“Africa is becoming very important within global markets as a production centre because of those competitive advantages,” says Duvall. “The problem is, who is controlling that, and who is generating wealth off of that?”

Lesotho leads the way

Nestled on a gentle plain amid the dramatic mountains of Lesotho, the Kolojane facility is the kind of place Ramaphosa had in mind when he talked about the enormous cannabis progress of South Africa’s neighbour. Under a vast translucent hail net, thousands of cannabis plants – some up to 4m high – soak up the country’s abundant sunshine. Workers harvest and trim the plants using hands and machines, before the biomass is dried out and moved to the packaging room where it is inspected, weighed and bagged.

The site, owned and operated by Cape Town-based Highlands Investments, includes a centre for fertigation, testing and data recording. In the current cycle, the firm will harvest 11 hectares, which managing director Mark Corbett expects will yield some 8.5 tonnes of THC (the principal psychoactive constituent of cannabis). From here, the product will be dispatched to the international medical and consumer markets.

Lesotho was one of the first African countries to grant licences for the cultivation of cannabis for medical and scientific purposes, and now stands as a model of how Africa’s cultivation ambitions can be realised, says Corbett.

“Certainly we can grow the cheapest globally. What we have as an advantage, especially as an outdoor grow, is we have cheap labour and we’ve got lots of space, lots of sun, a high altitude. We have the climate that enables us to be very cost competitive. We’re the same time zone as Europe, and geographically it’s much more convenient for us to ship into Europe. Language-wise with Commonwealth countries, we find there’s a lot of business that happens between us and the UK, and Europe.”

Those natural and situational advantages have attracted investor interest from further afield than South Africa. In mid-March, Akanda, a London-headquartered firm which owns the Bophelo Bioscience & Wellness cultivation campus in Lesotho, announced the completion of its initial public offering of 4m shares on the Nasdaq Capital Market. Initially offered at a price of $4 a share, the stock traded as high as $31 a share before settling at around $8.

The medical cannabis and wellness company, which owns an importer and distributor that supplies pharmacies and clinics in the UK, says it will use the proceeds primarily for property, plant and equipment, operations and working capital. CEO Tej Virk says that Lesotho’s advantages go beyond its natural environment and include a responsive regulatory regime and supportive industry ecosystem.

“Lesotho was the first country in Africa to license the cultivation and manufacturing of medical cannabis in 2017. It’s been a country apart and I think they’ve seized this opportunity to be a leader and by doing so at that stage, the country attracted a lot of capital. We have our operation positioned within a special economic zone in the Mafeteng region. And that affords us a lot of benefits, one of which is a lower rate of corporate taxation. The government is supporting us and they’re not trying to put up hurdles. This comes through in the way that we get responsiveness to anything that’s required for exporting our product.”

Better regulation needed

But finding a generous host country in which to cultivate is only part of the challenge of operating in a complex global cannabis supply chain defined by tangled regulation, exacting export standards and industrial-scale competition in the developed world, particularly North America. Navigating the market requires persistence and expertise, says Mark Corbett.

“I wish they would get some kind of global regulatory framework because it would make our lives a lot easier. Just the logistics of shipping for us is an absolute nightmare because every country it passes through, different regulations apply. Even within those jurisdictions, the regulators often don’t know what the regulations are. The customs authorities don’t know what the regulations are, so it makes moving product exceptionally difficult.”

While CBD-infused supplements tend to come under novel foods regulations in the UK for example, in South Africa such products may be listed as a complementary medicine with dosage limits restricting how much an individual can purchase. Companies have to apply individually to national regulators, and in some target countries just finding out which regulator is responsible for approving which product is a challenge.

In other markets it is abundantly clear which regulators hold sway – products for export to medical markets in Europe typically have to meet exacting scientific standards that only the best organised companies can hope to meet.

Unlocking value

The insistence on strict product uniformity demanded by global regulators often works against smaller-scale African farmers who cultivate outdoors, where controlling temperatures, soil toxins and other variables is much more challenging.

The result, says Duvall, is a “neocolonial” industry in Africa that largely services the export market but is divorced from the cultural context of historical cannabis cultivation and expertise in Africa itself. He says it is a model that excludes knowledgeable Africans at the expense of well-capitalised outsiders, and in which African seeds are bought at a pittance for cultivation in the global north.

“Structurally the global market and the legal market disadvantage regular people in Africa, South Asia and South America,” says Duvall. “In places that aren’t capital intensive it basically takes away that comparative advantage that Africa has of being able to grow multiple crops all year long. The energy and water demands of indoor production are insanely high and the way it’s controlled nowadays means it’s something more industrial than anything. It’s these genetic clones that have to be grown under these very specific conditions for uniformity. It’s this really weird hybrid of plant and industry.”

That has led African companies to carefully consider how they can unlock value. For Highlands, which last year merged with Goodleaf, a South African CBD brand with a portfolio of 30 products that are distributed in retail stores, coffee shops and online, the answer is a focus on specialised consumer and medical products rather than cannabis specifically tailored to the international medical smoking market. The firm offers skincare, food, beverages and supplements and is working with a partner on specialised medical products.

“We’re not looking to create that really curated beautiful smoking bud you’ll find in the German medical market, for example,” says Corbett. “This is much more geared around providing input into extraction, which is where the value chain is… I just don’t see old people with chronic pain rolling a joint. I think we’re going to move into where medicine is today with pills, inhalers, etc. So we’re positioning ourselves to provide very cost-effective high-THC products into those industries,” says Corbett.

Freeing the domestic market

A way to increase opportunities that is favoured by cultivators both large and small would be to free up African markets for domestic consumption. Several Southern African countries permit medical use, but none have fully legalised recreational use and the legal environment on the continent remains one of the most restrictive in the world.

South Africa, however, may be a harbinger of things to come. Gabriel Theron, CEO of South African cultivator Cilo Cybin and founder of Africa’s first cannabis-focused special purpose acquisition company, which is due to list on the JSE, says that there is a growing realisation that an export-only model is doomed to failure.

“I don’t believe that we’ve got a sustainable model when we are talking export only. What needs to happen is they need to de-schedule the THC levels and the CBD levels so that the recreational market can open up, so that your medicinal market can open up. Currently people can get access to the product, but it’s a prescription from a doctor, you need approval per patient for six months at a time, and you can’t move volume.”

That also has implications for foreign investment, he says: “If you have operations in North America, Europe, Australia, you would only open up in South Africa if you can get a hold of the local markets.”

Theron says regulators in South Africa and elsewhere should pursue a more agile regulatory system that is more flexible towards cannabis and other plant-based medicines. Recreational legalisation in particular would unlock a huge domestic market, he argues.

“Let the agricultural guys worry about the hemp production, put the recreational side the same as alcohol and tobacco, and the guys that want to create medicines, treat them as medicines. if you look at South Africa, we are quite far behind in terms of the global race. In my view, if you were to come in and say we’re going to open up all plant-based medicine research, because we can see that’s where the globe is moving, then a lot of these companies would come to South Africa to do the research, to set up manufacturing facilities, to do clinical trials.”

In recent months there has been dramatic progress. In March, the government tabled radical amendments to the Cannabis for Private Purposes Bill to allow for the licensed commercial cultivation and sale of cannabis for recreational purposes. The justice and constitutional development portfolio committee hopes to pass the bill by the end of April before it is sent for ratification by the upper house of the South African parliament.

Corbett, who is frustrated by tough South African regulations on CBD dosages in consumer products, says that such a “leapfrog” to a domestic recreational market would “put the country on the map”.

“Short-term, I think low-cost cultivation into a European supply chain [will be the model], but hopefully in time to come we can have our own industry that’s thriving. The consumption rates of cannabis in Africa are exceptional… We look at where resources are extracted from Africa with very little value, and we’d love it to be different for the cannabis industry.”

Building a brand

Value addition can take many forms. Historical strains of cannabis grown on the continent, such as Durban Poison and Malawi Gold, first gained a following in the illegal market and have now acquired a valuable form of brand recognition.

In a more flexible legal and regulatory environment, those countries could push for some kind of geographical indication in the same way that France protects champagne. Right now, valuable African varieties can be grown under lamps anywhere in the world with no benefit whatsoever to the communities from which they emerged.

“There is potential that people in Africa can produce local varieties based on local knowledge,” says Duvall. “In addition to participating more actively in directing and making decisions about the production of export varieties, lots of Africans know a lot about industrial agriculture and export markets. But just in terms of access to capital and being in positions of power, they’re disadvantaged relative to some company coming in from Israel or Canada with a bunch of money to invest.”

Theron agrees that Africa must offer more if its producers are to thrive in an increasingly commoditised global market.

“In a few years from now, people that didn’t create a brand in the cannabis space are going to be just your farmers. Unless you have created a brand for a flower, a specific strain or whatever the case, or you have created a brand for final products, you are not going to survive in this industry.”

Duvall says that truly unlocking the industry’s value will require African countries to take a leadership role in global debates around cannabis regulation and legalisation – a process which necessarily must first tackle the continent’s own stringent restrictions on the plant.

“What there needs to be is an actual African legalisation where the terms, the processes, the agricultural practices, the decision-making needs to be controlled in Africa, by Africans, rather than it just being some company that goes in and says, we’ll pay $70,000 for an annual licence. There has to be a different kind of approach.”